Anand Patwardhan has been making political documentaries for nearly three decades pursuing diverse and controversial issues that are at the crux of social and political life in India. Many of his films were at one time or another banned by state television channels in India and became the subject of litigation by Patwardhan who successfully challenged the censorship rulings in court. Patwardhan received a B.A. in English Literature from Bombay University in 1970, won a scholarship to get another B.A. in Sociology from Brandeis University in 1972 and earned a Master’s degree in Communications from McGill University in 1982. Patwardhan has been an activist ever since he was a student — having participated in the anti-Vietnam War movement; being a volunteer in Caesar Chavez’s United Farm Worker’s Union; working in Kishore Bharati, a rural development and education project in central India; and participating in the Bihar anti-corruption movement in 1974-75 and in the civil liberties and democratic rights movement during and after the 1975-77 Emergency. Since then he has been active in movements for housing rights of the urban poor, for communal harmony and participated in movements against unjust, unsustainable development, miltarism and nuclear nationalism. [Image Courtesy: Icarus Films, Bio Courtesy: Official Site]

The most acclaimed Indian documentary filmmaker, Anand Patwardhan has been called the Michael Moore of India, although the latter started his career much later than Patwardhan did. The comparison is not entirely unwarranted though. For one, Patwardhan’s political inclination is very similar to that of the Canadian-American. He even admires Moore’s works to a large extent. But of more interest is the commonality between their styles. Like in the films of Moore, the image and the sound counterpoint each other at the most critical junctures. But, unlike in Moore where it’s almost exclusively played out for laughs, this friction is also used to provide highly affecting social ironies or even serve as penetrating summations. Same is true of the dialectical imagery – arrived at though Eisensteinian cutting or, more frequently, within the same shot – in his films. This might sound too crude and simplistic, but Patwardhan’s curious, clear-sighted camera and editing never once call attention to themselves or invite us to marvel their artistry. It is almost as if the sound and the image have independent existence since each of them has its own emotional weight and rumination quotient. At times, the image and sound are linked together by folk (generally recorded directly) or pop songs (official versions), which serve as catharsis for the pent up resentment and tension. Moreover, these folk songs also help illustrate how a community uses its art forms to make a record of its problems and struggles and to develop a sense of clanship among its members to help them go on.

Another singular aspect of Patwardhan’s cinema is his attention to dialects, language and speech patterns. Although there must have been considerable amount of luck in making many of these observations, the amazing consistency with which these nuggets steal the speeches they appear in makes this an ostensible trademark of the director. A chief nuclear scientist believes, albeit with a modicum of humour, that the numerous berserk cows did not spoil the nuclear test because they are sacred. A well-off, educated urban businessman, who has, along with his wife, resorted to religious methods for having a child, tells us (among other atrocities) that Hinduism is extremely liberal and broad minded in comparison to Islam and that “women cannot be divorced very easily”. An atheist (or secular) speaker of the Left uses the term “Lakshman Rekha” to denote the poverty line. This scrupulous attention to representation extends also to the visual language. Mass media, especially mainstream cinema and popular television (shows and news – rather interchangeable really), make regular appearances in Patwardhan’s films and are used to highlight their regressive influence. Although the working methods that he has developed over time bear an unmistakable authorial stamp (save for two rather ordinary short films), Patwardhan claims that he does not believe in deliberate stylization and that there is no conscious aesthetic in his films. In fact, the only cinematic influence that he mentions in interviews is that of Imperfect Cinema (Patwardhan’s films are certainly works of Third Cinema and his essay on The Battle of Chile (1977) is an illuminating read). So it should of little doubt that his politics is what informs his aesthetics.

In a way, Anand Patwardhan could be called the child of Karl Marx and Karamchand Gandhi. If there is one vein that runs throughout Patwardhan’s filmography, it is the attempt to suitably wed class consciousness with nonviolent methods of problem solving. In that respect, all his films could be seen as efforts to demonstrate that this marriage is not just chimerical utopianism, but a practical possibility. He has been criticized for taking sides, for not presenting facts with objectivity and, plainly, for not giving the ‘other’ side a fair hearing. Surely, there can be few qualities more repulsive than non-committedness, neutrality and pseudo-objectivity in a political documentary for you can’t be neutral on a moving train. But then that doesn’t mean films such as Patwardhan’s are propagandistic or, worse, merely personal preferences, worldviews and opinions. His filmmaking is defined by curiosity and compassion rather than didacticism and judgment. Patwardhan’s allegiance is not to any geography, religion, ideology, language or class, but only to humanitarianism (for the lack of a better term), although, ironically, that stance dictates much of his politics. Through the films, it becomes evident that it is not an hatred towards the ruling class, but a genuine concern for the underprivileged that characterizes his cinema. Witness to this attitude is the fact his central interest remains – and this has given birth to the best sections he’s ever done – in the struggles of the oppressed than the acts of the powerful. All his films, in one way or the other, are celebrations of (or pleas for) nonviolent forms of resistance. (He places Mohandas Gandhi, Martin Luther King, B. R. Ambedkar and Salvador Allende on the same pedestal.) It is as if, for him, the struggle itself is more important than the end result. These films testify to the filmmaker’s belief that a struggle for human rights need not necessarily entail dehumanization of oneself, that, to borrow Gandhi’s oft-used quote, “an eye for an eye makes the whole world blind”.

(NOTE: As usual, there are gaping holes here which will be filled once I see those missing films)

Zameer Ke Bandi (Prisoners Of Conscience, 1978)

Shot on grainy 16mm stock that embodies the spirit and theory of Imperfect Cinema that Patwardhan so cherishes, Prisoners of Conscience (1978) captures a particular facet of the tumultuous years following the declaration of emergency by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in June, 1975: political imprisonment. Through first hand accounts, the director presents details of the appalling brutality of prison procedures and the classism that permeates them. Patwardhan’s major lament is not against Indira’s policies per se, but the very act of holding political prisoners without trial (That the film clearly points out that the situation did not improve much even after Janata Dal came to power testifies to its “nonpartisan” quality). What was unique about the widespread resistance to this political ploy of Indira Gandhi was that it was highly democratic in nature, with participation by both the secular Left and the Hindu-based RSS (a marriage quite unimaginable now), both workers and students, both citizens and immigrants and both radical Maoists and nonviolent Gandhians. Using the various interviews of people from each of these groups, Patwardhan attempts to examine and evaluate his own political leaning by trying to uncover socialist strains in Gandhian philosophy and the possibility of having a nonviolent base for Marxist thought. In additional to his ideology, it is also Patwardhan’s directorial style that seems to have (more or less) found its bearings in Prisoners as is evident in the therapeutic use of folk songs, the ironic cross cutting between Republic Day celebrations and prison proceedings and the general hesitation to be overly acerbic or coldly academic.

Shot on grainy 16mm stock that embodies the spirit and theory of Imperfect Cinema that Patwardhan so cherishes, Prisoners of Conscience (1978) captures a particular facet of the tumultuous years following the declaration of emergency by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in June, 1975: political imprisonment. Through first hand accounts, the director presents details of the appalling brutality of prison procedures and the classism that permeates them. Patwardhan’s major lament is not against Indira’s policies per se, but the very act of holding political prisoners without trial (That the film clearly points out that the situation did not improve much even after Janata Dal came to power testifies to its “nonpartisan” quality). What was unique about the widespread resistance to this political ploy of Indira Gandhi was that it was highly democratic in nature, with participation by both the secular Left and the Hindu-based RSS (a marriage quite unimaginable now), both workers and students, both citizens and immigrants and both radical Maoists and nonviolent Gandhians. Using the various interviews of people from each of these groups, Patwardhan attempts to examine and evaluate his own political leaning by trying to uncover socialist strains in Gandhian philosophy and the possibility of having a nonviolent base for Marxist thought. In additional to his ideology, it is also Patwardhan’s directorial style that seems to have (more or less) found its bearings in Prisoners as is evident in the therapeutic use of folk songs, the ironic cross cutting between Republic Day celebrations and prison proceedings and the general hesitation to be overly acerbic or coldly academic.

Hamara Shahar (Bombay, Our City, 1985)

Bombay, Our City (1985) is a devastating account of the slum clearance operations of the Bombay Municipal Corporation in 1984, in which encroachments by rural immigrants were systematically removed to make way for skyscrapers and to prettify the city. Patwardhan interviews residents of the slums, industrialists in the city, officials at the municipality office and middle class citizens of the city, all of whose words provide a unique insight into the issue. Occasionally, the film falls prey to an unrefined Marxist impulse wherein the director includes images of bourgeois tea parties and yacht races for no reason other than to provide contrast. But then, this sudden shift of gears also seems justified when we witness a group of upper-class folks – the city’s police commissioner included – discussing how to fight this “evil” of encroachments through martial training of youths. What is really extraordinary about the segments involving the slum residents is how remarkably aware these people are of their surroundings and of the numerous forces that bind them. A terrific song compiled by the local theatre group, which forms the spiritual backbone of the film, details the government’s injustices with great humour and pathos. Equally piercing are the testaments of the evicted (One of them says “Instead of removing poverty, they’re removing the poor”, alluding to Indira (and Rajiv) Gandhi’s populist slogan for eradicating poverty). Finally, Bombay, Our City also presents Patwardhan finding his own place as a filmmaker and an activist. One of the slum dwellers accuses Patwardhan of exploiting their misery for artistic gains while the Right accuses him of romanticizing the working class. The director, however, remains the humble inquisitor.

Bombay, Our City (1985) is a devastating account of the slum clearance operations of the Bombay Municipal Corporation in 1984, in which encroachments by rural immigrants were systematically removed to make way for skyscrapers and to prettify the city. Patwardhan interviews residents of the slums, industrialists in the city, officials at the municipality office and middle class citizens of the city, all of whose words provide a unique insight into the issue. Occasionally, the film falls prey to an unrefined Marxist impulse wherein the director includes images of bourgeois tea parties and yacht races for no reason other than to provide contrast. But then, this sudden shift of gears also seems justified when we witness a group of upper-class folks – the city’s police commissioner included – discussing how to fight this “evil” of encroachments through martial training of youths. What is really extraordinary about the segments involving the slum residents is how remarkably aware these people are of their surroundings and of the numerous forces that bind them. A terrific song compiled by the local theatre group, which forms the spiritual backbone of the film, details the government’s injustices with great humour and pathos. Equally piercing are the testaments of the evicted (One of them says “Instead of removing poverty, they’re removing the poor”, alluding to Indira (and Rajiv) Gandhi’s populist slogan for eradicating poverty). Finally, Bombay, Our City also presents Patwardhan finding his own place as a filmmaker and an activist. One of the slum dwellers accuses Patwardhan of exploiting their misery for artistic gains while the Right accuses him of romanticizing the working class. The director, however, remains the humble inquisitor.

Una Mitran Di Yaad Pyaari (In Memory Of Friends, 1990)

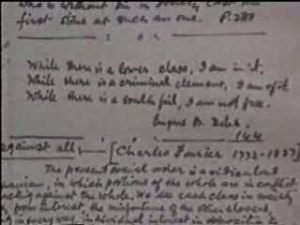

In Memory of Friends (1990) finds Patwardhan in Punjab covering communal clashes between Sikh and Hindu fundamentalists during the Khalistan Movement and the subsequent endeavours of secular parties with Marxist associations in reinstating peace in the state. The subject of In Memory is both philosophically and politically complex (primarily due to different parties holding power at the state and central levels), for the demand for a separate state based on religion is, as Patwardhan remarks, both purely democratic and against democracy. At the focal point of the film is the figure of Bhagat Singh, freedom fighter and revolutionary whose image has been appropriated and manipulated by each political group to suit to its own ideological agenda. The Sikh separatists claim Bhagat Singh was a religious man whereas the right wing extols his nationalism. Even those who remain neutral about him seem to consider him as some sort of an antithesis to the nonviolent Gandhi. This starling rupture between the past and the present – the reality and its image – informs the central structuring device of In Memory. Interleaved with footage of interviews with the secularists, the separatists and the relatives of Bhagat Singh are passages in which Bhagat Singh’s posthumously published jail writings are recited by a narrator (Naseeruddin Shah) which clearly indicate that he was not only a staunch socialist and an atheist who believed that widespread class consciousness was the only way out of communal wars, but also that he deeply admired non-violence. Like all the secular teachings of Sikhism, Bhagat Singh’s beliefs, too, seem to have vanished into the past.

In Memory of Friends (1990) finds Patwardhan in Punjab covering communal clashes between Sikh and Hindu fundamentalists during the Khalistan Movement and the subsequent endeavours of secular parties with Marxist associations in reinstating peace in the state. The subject of In Memory is both philosophically and politically complex (primarily due to different parties holding power at the state and central levels), for the demand for a separate state based on religion is, as Patwardhan remarks, both purely democratic and against democracy. At the focal point of the film is the figure of Bhagat Singh, freedom fighter and revolutionary whose image has been appropriated and manipulated by each political group to suit to its own ideological agenda. The Sikh separatists claim Bhagat Singh was a religious man whereas the right wing extols his nationalism. Even those who remain neutral about him seem to consider him as some sort of an antithesis to the nonviolent Gandhi. This starling rupture between the past and the present – the reality and its image – informs the central structuring device of In Memory. Interleaved with footage of interviews with the secularists, the separatists and the relatives of Bhagat Singh are passages in which Bhagat Singh’s posthumously published jail writings are recited by a narrator (Naseeruddin Shah) which clearly indicate that he was not only a staunch socialist and an atheist who believed that widespread class consciousness was the only way out of communal wars, but also that he deeply admired non-violence. Like all the secular teachings of Sikhism, Bhagat Singh’s beliefs, too, seem to have vanished into the past.

Ram Ke Naam (In The Name Of God, 1992)

In the Name of God (1992) chronicles the immediate and historical events leading up to the demolition of the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh on 6 December 1992, when thousands of Hindu fundamentalists barged into the mosque premises and started bringing down the structure. Characteristically witty with a very keen eye for tragicomic ironies (The camera casually photographs an eatery named “Shriram Fast Food” as we hear public speakers, mounted on hired trucks, advertising the divinity of Lord Ram), Patwardhan examines the classism that exists within these communal forces (in the form of castes) and charts both the strategies of the then-oppositional Hindu groups, one of whose leaders had undertaken a nationwide propagandist tour, and the efforts of the secular Left in mitigating the communal agitation that seemed to have gripped the country like a plague. Unlike most rationalists, he chooses to view religion not as an entity fascist in its very conception, but as one which is molded by the ideology that propagates it. This is reinforced by the numerous segments featuring with Pujari Laldas, the official priest at the temple inside the mosque premise and a Hindu liberation theologian, the honesty and conviction of whose words suffuse the film with an earnestness and compassion so crucial to sociological filmmaking. But perhaps more than anything, In the Name of God is an elegy for the city of Ayodhya – a city caught unawares by external polarizing forces, its identity erased and reconstituted and its people made to live in perpetual fear.

In the Name of God (1992) chronicles the immediate and historical events leading up to the demolition of the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh on 6 December 1992, when thousands of Hindu fundamentalists barged into the mosque premises and started bringing down the structure. Characteristically witty with a very keen eye for tragicomic ironies (The camera casually photographs an eatery named “Shriram Fast Food” as we hear public speakers, mounted on hired trucks, advertising the divinity of Lord Ram), Patwardhan examines the classism that exists within these communal forces (in the form of castes) and charts both the strategies of the then-oppositional Hindu groups, one of whose leaders had undertaken a nationwide propagandist tour, and the efforts of the secular Left in mitigating the communal agitation that seemed to have gripped the country like a plague. Unlike most rationalists, he chooses to view religion not as an entity fascist in its very conception, but as one which is molded by the ideology that propagates it. This is reinforced by the numerous segments featuring with Pujari Laldas, the official priest at the temple inside the mosque premise and a Hindu liberation theologian, the honesty and conviction of whose words suffuse the film with an earnestness and compassion so crucial to sociological filmmaking. But perhaps more than anything, In the Name of God is an elegy for the city of Ayodhya – a city caught unawares by external polarizing forces, its identity erased and reconstituted and its people made to live in perpetual fear.

Pitra, Putra Aur Dharmayuddha (Father, Son And Holy War, 1994)

A twin to In the Name of God, Father, Son and Holy War (1994) is less topical and more contemplative a film than its predecessor in that it attempts to study primeval and deep-rooted social issues with the bloody aftermath of the Babri Mosque demolition as only the backdrop. The central thesis of the film contends that religion and mythology – whatever be their flavour – construct and propagate a skewed sense of masculinity and bravery that is predicated on violence and hatred, which deems non-violence as an impotent principle and which is only exacerbated by most of modern consumerist advertising and certain sections of the mass media. Furthermore, Patwardhan suggests, it is the same texts and practices that define femininity as whatever masculinity isn’t, with passive acceptance, chastity and servility being its prime virtues. The film argues, presenting archaeological evidence, that this was not always the case and that, at the danger of sounding too simplistic, this worship of violence and destruction – in place of fertility and proliferation – started when man learned to domesticate and own animals and settle down. Equally sweeping are its other assertions that attempt to cover of number of social phenomena (including the popularity of WWF and on-screen violence, in general), which runs the risk of decontextualizing the key argument of the film. True, that all these facets are only deeply intertwined, but the film is so ambitious and loosely structured that it almost ends up proving otherwise. These observations would find greater strength and coherence in the director’s decidedly superior work, War and Peace.

A twin to In the Name of God, Father, Son and Holy War (1994) is less topical and more contemplative a film than its predecessor in that it attempts to study primeval and deep-rooted social issues with the bloody aftermath of the Babri Mosque demolition as only the backdrop. The central thesis of the film contends that religion and mythology – whatever be their flavour – construct and propagate a skewed sense of masculinity and bravery that is predicated on violence and hatred, which deems non-violence as an impotent principle and which is only exacerbated by most of modern consumerist advertising and certain sections of the mass media. Furthermore, Patwardhan suggests, it is the same texts and practices that define femininity as whatever masculinity isn’t, with passive acceptance, chastity and servility being its prime virtues. The film argues, presenting archaeological evidence, that this was not always the case and that, at the danger of sounding too simplistic, this worship of violence and destruction – in place of fertility and proliferation – started when man learned to domesticate and own animals and settle down. Equally sweeping are its other assertions that attempt to cover of number of social phenomena (including the popularity of WWF and on-screen violence, in general), which runs the risk of decontextualizing the key argument of the film. True, that all these facets are only deeply intertwined, but the film is so ambitious and loosely structured that it almost ends up proving otherwise. These observations would find greater strength and coherence in the director’s decidedly superior work, War and Peace.

A Narmada Diary (1995)

A very pertinent film about the social conditions in the third world – especially after the advent of globalization – A Narmada Diary (1995) sits well alongside works such as West of the Tracks (2003) and Up the Yangtze (2007) in the sense that it chooses to document on film – for us and for posterity – what would otherwise be relegated to the footnotes of most mass media. Co-directed with activist Simantini Dhuru, the film tracks the struggle of an indigenous population (Narmada Bachao Andolan/Save Narmada Movement) living on the banks of river Narmada against the Sardar Sarovar Dam project, which would result in their displacement and massive land submergence. There is a sense of watching history in the making as the group congregates for planning, organizes non-violent protests, confronts key officials responsible for the construction of the dam and exhibits a singular integrity of purpose, further evidencing Patwardhan’s heartfelt admiration for Patricio Guzmán’s masterpiece. Although the Save Narmada Movement is generally known to be led by Medha Patkar, Patwardhan and Dhuru avoid the pitfall of making a hero out of her and building a film around an exceptional individual’s actions. Instead, true to the spirit of this struggle, the directors present her as a key player in a movement organized and executed by the local populace en masse. Additionally, A Narmada Diary is also a personal struggle for Patwardhan as a filmmaker. Like the rebellion, his work stands as the direct antithesis to the pro-dam government propaganda films that make their appearance throughout the picture.

A very pertinent film about the social conditions in the third world – especially after the advent of globalization – A Narmada Diary (1995) sits well alongside works such as West of the Tracks (2003) and Up the Yangtze (2007) in the sense that it chooses to document on film – for us and for posterity – what would otherwise be relegated to the footnotes of most mass media. Co-directed with activist Simantini Dhuru, the film tracks the struggle of an indigenous population (Narmada Bachao Andolan/Save Narmada Movement) living on the banks of river Narmada against the Sardar Sarovar Dam project, which would result in their displacement and massive land submergence. There is a sense of watching history in the making as the group congregates for planning, organizes non-violent protests, confronts key officials responsible for the construction of the dam and exhibits a singular integrity of purpose, further evidencing Patwardhan’s heartfelt admiration for Patricio Guzmán’s masterpiece. Although the Save Narmada Movement is generally known to be led by Medha Patkar, Patwardhan and Dhuru avoid the pitfall of making a hero out of her and building a film around an exceptional individual’s actions. Instead, true to the spirit of this struggle, the directors present her as a key player in a movement organized and executed by the local populace en masse. Additionally, A Narmada Diary is also a personal struggle for Patwardhan as a filmmaker. Like the rebellion, his work stands as the direct antithesis to the pro-dam government propaganda films that make their appearance throughout the picture.

Jang Aur Aman (War And Peace, 2001)

War and Peace (2001) could well have been titled War and Peace: Or How I Learned to Forget Gandhi and Worship the Bomb, for the major theme that runs through the film is the disjunction that exists between the past and the present and a nation’s collective (and selective) cultural amnesia with respect to its own past. Shot in four countries – India, Pakistan, Japan and the USA – and over a period of four years following the 5 nuclear tests done by India in 1998, Patwardhan’s film was slammed by Pakistan for being anti-Pakistani and by India for being anti-Indian, while the film’s barrel was always pointed elsewhere. Tracing out the country’s appalling shift from Gandhianism to Nuclear Nationalism and Pakistan’s follow-up to India’s nuclear tests, Patwardhan examines the role of the two countries as both perpetrators and victims of a major mishap that is now imminent, taking the Hiroshima-Nagasaki incident as a potent example to illustrate why nuclear armament is not merely a potentially hazardous move, but a wholly unethical one. War and Peace is a film that should exist, even if amounts to only the ticking of a radiometer amidst atomic explosions, for it calls for a realization that there can be neither a victor nor a finish point in this internecine race. It is, without doubt, Anand Patwardhan’s masterpiece. [Read full review]

War and Peace (2001) could well have been titled War and Peace: Or How I Learned to Forget Gandhi and Worship the Bomb, for the major theme that runs through the film is the disjunction that exists between the past and the present and a nation’s collective (and selective) cultural amnesia with respect to its own past. Shot in four countries – India, Pakistan, Japan and the USA – and over a period of four years following the 5 nuclear tests done by India in 1998, Patwardhan’s film was slammed by Pakistan for being anti-Pakistani and by India for being anti-Indian, while the film’s barrel was always pointed elsewhere. Tracing out the country’s appalling shift from Gandhianism to Nuclear Nationalism and Pakistan’s follow-up to India’s nuclear tests, Patwardhan examines the role of the two countries as both perpetrators and victims of a major mishap that is now imminent, taking the Hiroshima-Nagasaki incident as a potent example to illustrate why nuclear armament is not merely a potentially hazardous move, but a wholly unethical one. War and Peace is a film that should exist, even if amounts to only the ticking of a radiometer amidst atomic explosions, for it calls for a realization that there can be neither a victor nor a finish point in this internecine race. It is, without doubt, Anand Patwardhan’s masterpiece. [Read full review]

[To The Children Of Swat, From The Children Of Mandala (2009)]